We’ve been told more megapixels are better. But is it true? Well, megapixels are a crucial component of excellent image quality, right up until the point they make your photos look worse.

Thus, buying a new camera or smartphone with more megapixels than your last could be a poor move. Here’s why. Jump to Conclusion

Table of Contents

- What is a megapixel?

- Why more megapixels is better

- Why more megapixels are worse

- More Megapixels for Marketing

- Conclusion

What is a megapixel?

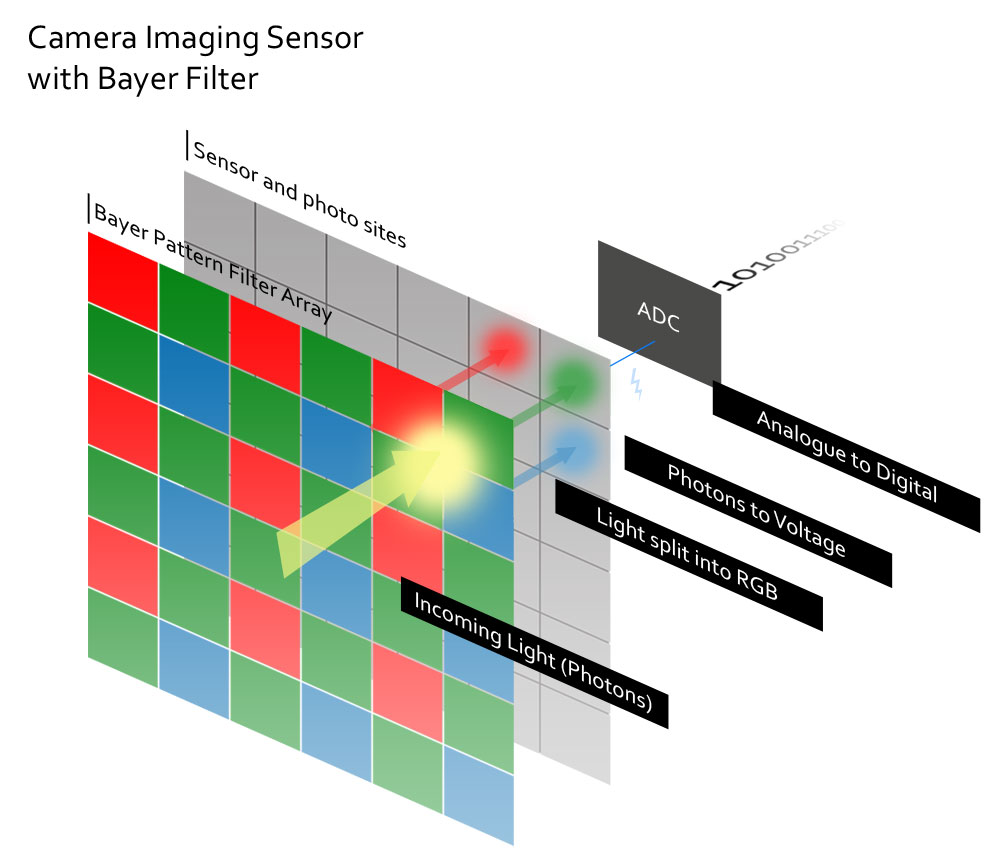

A megapixel denotes one million pixels; the more megapixels you have, the larger your photo will be, and the greater the potential to capture more detail. For every single pixel, your camera’s sensor has a photo site. Photo sites are best imagined as tiny wells that collect light and produce small electrical charges.

Specifically, the more light a photo site receives, the stronger the electrical current will be and the brighter your photo’s pixel. Multiply this process by a few million pixels and assemble them, and you end up with a photograph.

Why more megapixels is better

Each pixel is a small square of a single color and quite useless on its own. Thus, you need many pixels or megapixels to form an image. The more megapixels you have, the more detailed your photo will be. For instance, more megapixels means you’re more likely to see the fine detail on a bird’s feathers or be able to separate individual blades of grass.

As you might expect, you’ll soon run into diminishing returns. While the first few megapixels are essential for producing something that looks like an image, you might not even be able to notice the difference between 30 and 50 megapixels.

More megapixels for printing

However, large megapixel counts have utility. For instance, you might want to convert your photos into large prints, and generally speaking, the more megapixels you have, the larger your print will be. Many photos are printed using 300 pixels per inch. Therefore, you’ll need 2.2 megapixels to produce a 6×4-inch print or 35 megapixels for a large 24×16-inch print of equal detail. If printing big, you should take advantage of today’s best AI upscaler applications.

HIGHLIGHTED SOFTWARE DEAL – ARTICLE CONTINUES BELOW

TOPAZ PHOTO AI 2

NOW US$199. READ TOPAZ PHOTO AI REVIEW

More megapixels for cropping

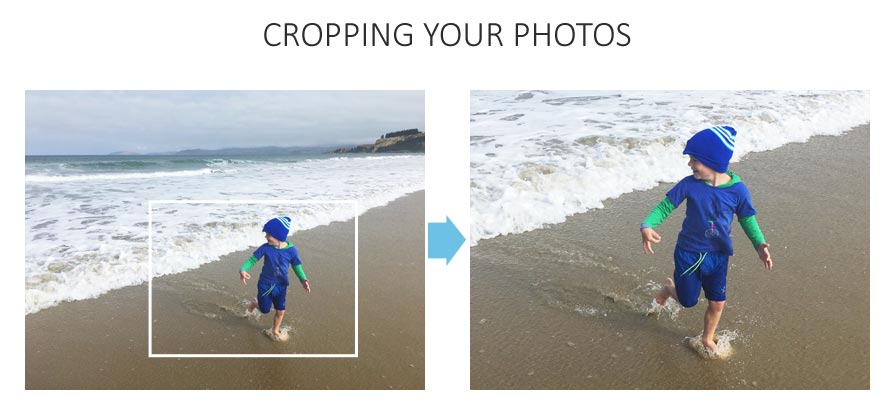

Alternatively, you might wish to crop your photos to a better composition. Since cropping results involves binning megapixels, you might as well begin the process with as many megapixels as possible.

Why more megapixels are worse

High megapixel counts offer most users diminishing returns. But too many megapixels produce negative returns. In other words, image quality grows worse.

Worse image quality

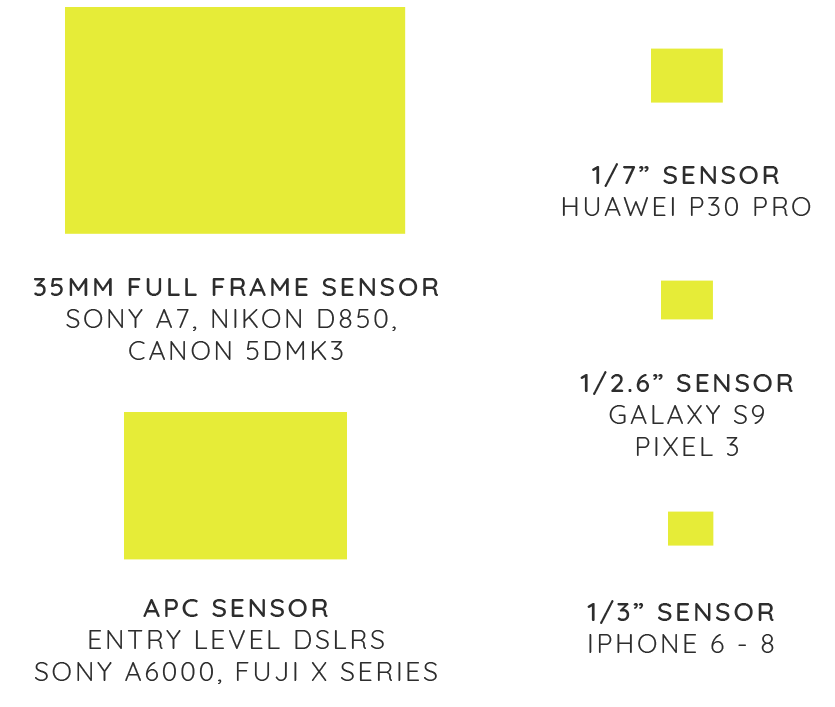

The higher your camera’s megapixel count, the more photo sites your sensor must have. The best way to create room for more photo sites is to use a larger sensor like those installed inside advanced mirrorless cameras.

But more often than not, particularly in the case of smartphones, they shrink the photo sites so they crowd more into the same amount of space. This has resulted in tiny sensors being overcrowded with photosites, which is detrimental to image quality for two reasons.

More megapixels equal more noise.

If we consider a photo site a well for light, shrinking the well reduces its capacity for light. This is problematic since light is a key ingredient in a photo. Since each pixel receives less light, it produces less electrical current—known as a signal. Less signal equals more noise and poorer image quality.

While noise itself is destructive, so is the technology to remove it. In most cases, noise reduction strips detail and, at worst, heavy-handed noise reduction can make your photo look like an oil painting. Check out my list of best noise reduction software if you have some noisy photos to fix.

More megapixels require better lenses.

A high-resolution sensor with densely packed photo sites needs a high-resolution lens. After all, even with perfect vision, you’ll struggle to see through a dirty windscreen.

Fortunately, high-quality lenses are available for high-end mirrorless and DLSR. Unfortunately, they are big, heavy, and expensive.

Naturally, smartphones lack the capacity for a large, heavy, and expensive high-quality lens and must make do with something more practical. Ironically, however, due to their tiny high-resolution sensors, they need a higher-quality lens than most.

More Megapixels for Marketing

Today, the main benefit of increasing the number of megapixels is marketing. Fortunately, megapixel marketing has not overtaken the enthusiast camera market as its customers tend to know better. Thus, spending thousands of dollars on a camera with ‘just’ 24 megapixels is common enough.

However, this is not the case with smartphones. For many, the term megapixels is synonymous with image quality, and one of the easiest ways for a smartphone manufacturer to differentiate its new smartphone from its last is to increase its megapixel count.

Broadly speaking, any smartphone made today already has too many megapixels. Therefore, there’s no need to base your next upgrade on megapixels alone.

Get Discounts on Photo Editing Software

Subscribe to my weekly newsletter and be notified of deals and discounts on photography software from ON1, Adobe, Luminar, and more. Spam Promise: Just one email a week, and there’s an unsubscribe link on every email.

Conclusion

More megapixels do equal better image quality, but only to a point. After this point, the value of more megapixels diminishes and is limited to specific use cases, such as making large prints or heavy cropping.

But when an image sensor delivers too many megapixels, image quality drops, and noise increases, resulting in a poorer, muddier, and noisier photo.

Unfortunately, for many, the term megapixels is synonymous with image quality; the more, the better. This presents an opportunity for smartphone manufacturers since increasing megapixels is one of the best ways to differentiate one phone from another.

In reality, smartphones have had enough megapixels for years and are held back by smaller, cheaper lenses and tiny light-starved sensors. Unfortunately, addressing either of these issues is problematic since a smartphone must remain compact, leaving an increased megapixel count the most viable ‘improvement.’

So, how many megapixels do you need? Well, 2 megapixels is plenty for social media or a high-quality 6×4 print. But 12 megapixels offer a good balance of quality and utility.

Subscribe to my weekly newsletter and be notified of deals and discounts on photography software and gear. Subscribe now.